By Christopher Justin Einolf

The world’s first conference on the abolition of torture drew more than 300 delegates representing over 70 countries and international organizations. It opened with the news that the United Nations General Assembly had passed a resolution condemning torture, along with a personal message from the U.N. secretary-general.

Amnesty International, the nonprofit human rights advocacy group that organized the conference, preceded it by releasing a report documenting torture in 65 countries and collecting over a million signatures of citizens from 91 countries asking the U.N. to outlaw torture.

The conference ended with an ambitious plan to end torture, including identifying the institutions and individuals responsible for torture, learning how and why torture happens, developing legal solutions, creating an International Court of Criminal Justice and providing medical treatment for torture survivors. That conference took place 50 years ago, in 1973. And still people torture each other.

As a sociologist who studies torture, I have spent years trying to learn what causes torture and how to prevent it. During my first career as a legal advocate for survivors of torture seeking asylum in the United States, I saw the terrible effects of torture on my clients. Physical scars were rare – most torturers are careful not to leave marks – but psychological scars were common, making it difficult and retraumatizing for survivors to tell their stories to the immigration judge.

Since then, I have studied how people become torturers, whether torture works, how it affects its victims and how to prevent it.

Five decades after that first anti-torture conference, a lot of work remains, particularly in preventing torture from happening in the first place. But there has been some progress, too.

An international effort

In 1973, the world was just beginning to learn how widespread torture actually was. Governments of all types used torture: the United Kingdom in Northern Ireland, the U.S. military in Vietnam, communist governments such as the Soviet Union and China, and right-wing dictatorships such as Argentina, Greece and Chile. Soldiers used torture against guerrilla opponents, police used torture against criminal suspects, and security forces used torture against political opponents.

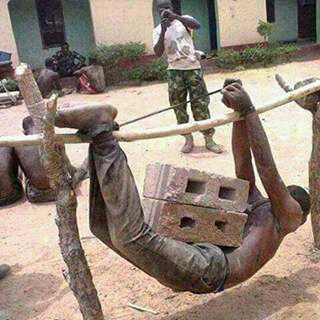

The stated purpose of torture was to get information and obtain confessions, but the real purpose of torture was to maintain power through fear. Then, as now, common torture methods included beatings, electric shock, rape, suspension from the ceiling and asphyxiation.

In 1984, after years of work by Amnesty International and other groups, the United Nations approved the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, placing an absolute ban on torture, with no exceptions, and providing legal protection for victims. Today, 173 countries of the world’s 195 have signed it, including the U.S.

Several U.N. entities, including the U.N. Committee Against Torture, the U.N. special rapporteur on torture and the U.N. subcommittee on prevention of torture, visit places of detention to document when torture happens and urge governments to prevent it. Amnesty International and many other human rights groups publish reports documenting torture and lobby governments to cease its practice.

The U.N. established special tribunals to try perpetrators of torture and other atrocities in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and in 2002 it established a permanent International Criminal Court. A host of treatment clinics, both in the United States and throughout the world, provide medical and psychological services to survivors.

But there are few signs that the situation is getting much better. While making an accurate estimate of the number of people tortured in the world is impossible, because torture is illegal and occurs in secret, the best available evidence suggests that torture has decreased over the past two decades, but only slightly.

What actually stops torture?

The United Nations and human rights organizations have tried many strategies to stop torture over the years. At the highest level, human rights organizations have lobbied elected officials in the United States and Europe to put diplomatic pressure on countries that use torture, including withholding trade rights and military aid. At the ground level, human rights workers have given human rights training to police officers, defense attorneys and judges, informing them of their obligations under international law.

It is difficult to say which strategies work best, because there is no good data to work with. Since torture happens in secret, accurately measuring the level of torture before and after an intervention is nearly impossible. Taking effective action against torture might even cause the number of reported torture incidents to increase, as human rights workers get better at detecting it and the news media does more to publicize it.

Human rights scholars differ in their opinions on what strategies work, or even whether anti-torture strategies work at all. When scholars study individual countries in depth, they often see that interventions by human rights nonprofits have a positive effect. But when comparing many countries statistically over time, scholars often see little effect of anti-torture advocacy.

The act of signing on to the U.N. Convention Against Torture seems to have little effect. Torturing governments may sign the convention as a way of gaining international approval, with no intention of changing their actual practices. This is easy, because the convention has no binding enforcement system and does not require countries to permit independent monitoring. Instead, countries report their own actions.

However, some countries have signed an optional additional part of the convention, which commits them to accepting U.N. monitoring visits. Those countries do seem to reduce their use of torture. While most countries in Europe and Latin America and many in Africa have signed this optional protocol, the United States has not.

Many human rights organizations follow a strategy of “naming and shaming” – documenting and reporting torture in well-researched reports and calling out the countries that allow it to happen.

Studies differ in their assessment of whether these efforts work, and some have even found negative side effects, as governments may reduce their use of torture but increase other human rights violations, including political imprisonment, extrajudicial executions and restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly.

The naming-and-shaming strategy seems to work in some circumstances, such as in countries making the transition from autocracy to democracy, countries that have an active domestic human rights movement, or in cases where the governments of powerful countries provide additional pressure.

Some progress

The news is not all bad, however. In 2015, the international anti-torture nonprofit Association for the Prevention of Torture funded a team of researchers to analyze the effectiveness of a number of torture prevention strategies.

They found that some basic changes in the practices followed after an arrest of a criminal suspect can make a big difference, such as outlawing unofficial detention, notifying family members about arrests, providing access to a lawyer, mandating timely presentation of the suspect before a judge, performing medical exams and recording interrogations. Sending independent observers to visit places of detention, launching criminal prosecutions of torturers and establishing an independent human rights ombudsman’s office helped as well.

In conclusion, efforts by the U.N. and human rights nonprofits have not ended torture. But that doesn’t mean their work is not worthwhile. Documenting torture and bringing it to the attention of policymakers and the public is an important first step. Scientific research is now helping us learn what causes torture and evaluate what strategies work to prevent it. The end of torture still lies far in the future, but it is achievable with sustained and informed effort.

Christopher Justin Einolf is an associate Professor of Sociology, Northern Illinois University